Not only do I touch wood, but wood also touches me – interview with Grzegorz Hańderek

Grzegorz Hańderek is a professor of fine arts and the rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. His work focuses on visual arts and graphic art. He has authored dozens of solo exhibitions. The artist has been supporting the idea of Xylopolis since the beginning of the project.

In an interview with Magdalena Lyżnicka-Sanczenko, acting director of the Centre for Wood Art and Science, Grzegorz Hańderek talks about whether art is eco-friendly, what the creative process is to him, why non-mainstream art can be more interesting, and what draws him to the regions of Suwałki and Podlaskie.

Enjoy the interview.

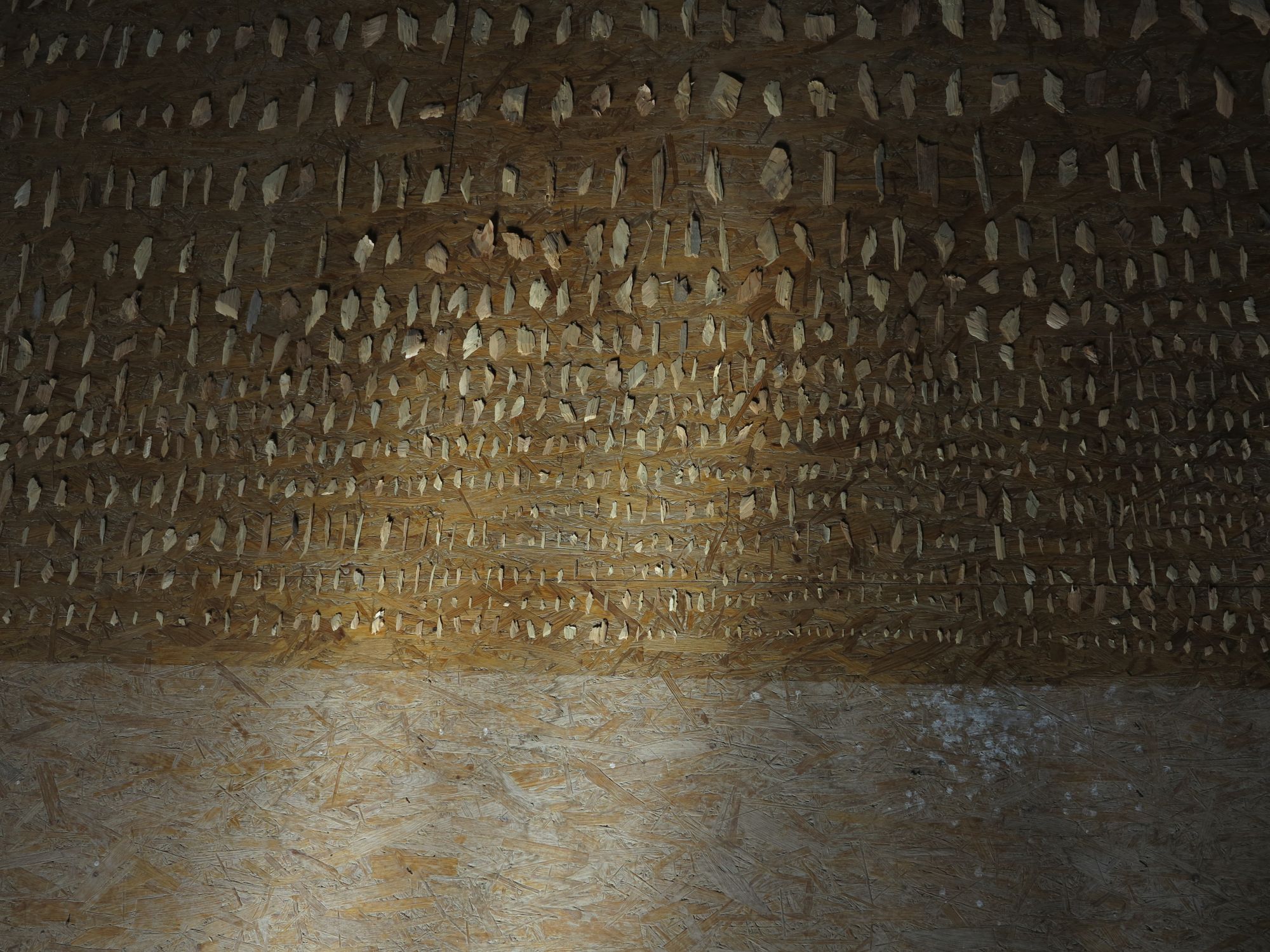

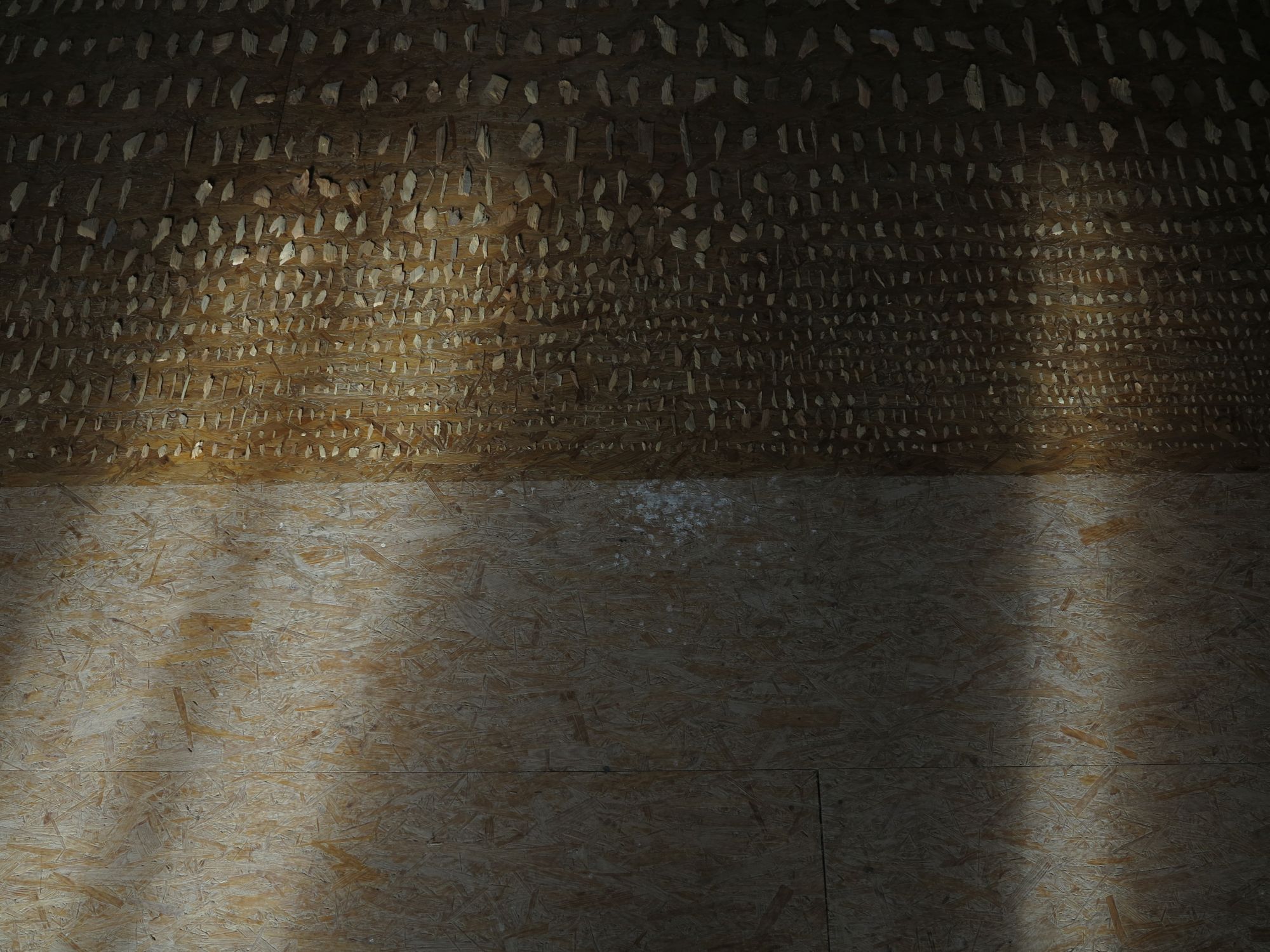

MŁS: Perhaps this will be a biased question, of the type: “What was the author's intention?”. But I can’t help but ask what you wanted to express by arranging an image from the wood chips that remained after the sculpture by Łukasz Gruszczyński. Is it possible to make art out of everything, even scrap?

GH: I think it would be very boring if the impact that art has was reduced only to the process of decoding the intention of the creator. Art (at least as I understand it) is a meeting of knowledge, experience, sensitivity, and the imagination of the creator and the recipient – it is a subjective, mutual, and thus open relationship.

The piece in Vierraden was created spontaneously, during a workshop – the impulse was accidental: I came across a sculpture left after one of the previous editions and the remains of the work of the sculptor in the form of chips that had not been cleaned up. The correspondence of these elements shifted my attention from the effect – the work of art – to the process and related issues. We usually treat sculpting as a process of shaping the form by processing some material. The final result – the sculpture – is therefore the result of overcoming the resistance of matter in order to extract the human idea. However, such a view/thought can extend beyond the field of art and cover our – often very positively motivated – drives or aspirations. I tried to capture this piece as a dialogue. The peculiar collection of shavings, leftovers, which constitute my piece, is on the one hand an attempt to draw attention to costs, and on the other – its form aggregates a trace of energy released during the process. Wood shavings are far more expressive than the sculpture. Their quantity and character encapsulate the brutal actions that are not as evident in the sculpture itself.

MŁS: You have shown then that the process of creation means overcoming the resistance of matter, and that from this remaining matter you can make something more. To me this refers to the ecological aspects of art. Can art be educational in terms of ecology?

GH: Maybe it should, and in a much wider sense than the generally accepted one. Both through the methods of work that it offers, but also all the visibility mechanisms it uses. This is especially important today, in times of irreversible changes that are ruining our ecosystem. Art can relieve this dramatically unpleasant message of the intrusive didacticism that, as we know, breeds resistance or is likely to face denial. All the more so because the necessary change is based on both learning and un-learning. Art can be “useful” in this respect, but it must reformulate its existing models of functioning, including going beyond the exclusive and safe bubble in which it is stuck.

Coming back to the previous topic, this also requires a change at the level of language: Saying, for example, “working with wood” instead of “working in wood”. This shift hints at a specific type of communication/correspondence. The awareness that not only I touch the wood, but wood also touches me, in the sense that reality touches (or concerns) us. It allows us to go beyond individualistic, egoistic attitudes and feel that we are part of a larger whole. Such a change in consciousness and sensation is possible through the tools offered by creativity. This is perhaps best seen in music – when the full expression is obtained by tuning in with the instrument. This “tuning in” is especially important, or perhaps even alarming, when we see how this environment is exploited. Art can visualise those ideas that we’re completely “green” about.

MŁS: You appreciate working with wood, but what sort of inspiration does it give you?

GH: What inspires me is, above all, its multitudes of existence – as a living being that we share space with, and as material which, thanks to human thought and physical work, accompanies us in the form of a threshold, a table, a window, or a coffin. The tree/wood refers back to its own history – to the vitality of life, to time, with its cyclicality, but it also goes forward – to its destiny. But I like the tree/wood in the state where it does not represent anything, as it simply is. It can give you shelter; you can feel and hear it. Wood shapes empathic imagination – it stores life in its organic structure, thanks to which the functions we give it develop our sense-based experience. These simple experiences will not be replaced by simulations.

MŁS: Let’s go back to what you mention a moment earlier – about tuning in with the material, and that art should go beyond its bubble… My impression is that folk artists have always been outside this bubble and were close to the matter in which they worked. Maybe it's time we stopped dividing art into high art and folk/amateur art? Podlaskie is home to many folk artists, numerous sculptors working – as you say – “with” wood, just to mention Włodzimierz Naumiuk. Can professional artists find inspiration in the works of folk creators?

GH: It seems to me that this division has always been arbitrary and artificial (nomen omen). Today, the peripheries inhabited by outsiders are often much more interesting than the mainstream with its showrooms and rankings. The intuitions of the so-called non-professional artists (once also harshly referred to as naive art) are very liberal and often go far beyond, creating something akin to private mythologies. Their attitudes are an excellent example of the “tuning in” I mentioned. Today they are often inspirational in terms of fantastic, surrealist poetics, but their work cannot be reduced to a reference point for “mainstream art” because they remain in a lively discourse with it, based on equality/partnership.

The tree/wood refers back to its own history – to the vitality of life, to time, with its cyclicality, but it also goes forward – to its destiny. But I like the tree/wood in the state where it does not represent anything, as it simply is. It can give you shelter; you can feel and hear it.

MŁS: And about our region. Please tell me what draws you here?

GH: It’s hard to nail it down precisely. It’s a kind of natural, unpretentious force and truth that can be felt when you touch this place: the landscape and the fantastic, hospitable people – open and grounded, immersed in the area. Here I learn to regulate the inner chaos I bring with me, to set the right pace and to distinguish the natural, organic from the artificial. So I come here mainly to clear my mind of distractions and to be – in slow motion – with people dear to me, with whom relations have imperceptibly changed into bonds. This is, after all, the time for things there is usually no time for.

MŁS: Recently you took part in an interesting project in Krasnogruda near Sejny.

GH: Thanks to an invitation from Krzysztof and Małgorzata Czyżewski, I participated in a symposium titled “Poesis”. The idea of the “meadow of poetic meditation” focused around communal sensation based on the exchange of experiences, both those that clearly lie within the field of art and beyond it. The starting point was a reflection, according to which the condition of usefulness is to undertake internal work – spiritual, internal development in the act of serving other beings. Measuring the rhythms of poems by the time of the local woodpecker sometimes turns out to be very much needed.

MŁS: This sounds a bit puzzling. A similar non-obvious action is the Field Practice Laboratory?

GH: The idea of the Laboratory was born on the occasion of two exhibitions organised jointly with researchers from the University of Silesia and other centres: The first one, dedicated to the Silesian “anthropocene” river-not-a-river Rawa (the exhibition entitled “Subject: River” was an event accompanying the 2022 World Urban Forum in Katowice) and “Underground. Subterra incognita” at the BWA in Katowice in 2023. Both of these presentations aimed to show the potential of new narratives about this difficult heritage that we share in Silesia.

This alliance of scientists and artists involved in generating social change aims to concretise their activities in the form of a Field Practice Laboratory, which uses the tools of art that allow (or, sometimes, force) us to see, listen, feel and engage in ways different from what we are accustomed to. The laboratory is a meeting space, assuming different ways of working across, between and beyond disciplinary boundaries. This approach is rooted in the field as an open situation shaped by the dynamics and forces that in turn shape us. It is a project that moves beyond the limits of methodologies established by science and for science for radical artistic practice.

MŁS: To the layman, this may seem quite mysterious. Can you give an example of such field practice, or does it escape all descriptions and you just have to experience it?

GH: Our field practices are indeed difficult to name or grasp, although they are often very pragmatic in nature, involving the inclusion of non-artistic activities (often also including those that do not lead to the creation of a piece) into the field of art. Thus, we also include a growing group of people as participants. Moreover, the area of field research is not only present in the geographical place, but also extends to material, social and symbolic spaces — the perception (interaction through senses and emotions), learning, falling, wandering, working in the field: renovation, cleaning, processing, witnessing, fiction, writing, “displaying”/visualising. Field practices are intended to lead the search for the spirit of community. Their place is where so-called hard data and evidence fail.

MŁS: I immediately want to go with your group into the field. I hope that you will also reach us with your field laboratory, and we’ll get a chance to look for the spirit of community together. Thank you very much for the constructive conversation and I wish you the most interesting artistic realizations possible.

Thank you.

Conducted by

Magdalena Łyżnicka-Sanczenko

Photos

The portrait of Grzegorz Hańderek: Adam Lach

Archives of Grzegorz Hańderek